Does Mozart’s music deserve a place at a nuclear power plant?

Energy Northwest’s nuclear plant, the Columbia Generating Station, is the safest environment I’ve ever seen. Every precaution is taken to keep the employees protected from the omnipresent radiation. Everyone must wear a badge that monitors your exposure, protective gloves, goggles, a hard hat, even ear plugs for when the turbines get really noisy.

Many times during my tour I was required to pass through detectors to make sure that I was not at risk. And the plant itself is under constant measurement and surveillance to catch any irregularity. Ingenious procedures that have been fine-tuned over the half-century of nuclear power’s history are all in place.

This is an environment where errors that escape detection can spell disaster.

It’s understandable that their top leaders would be vigilant – verifying that the mid-level managers make the right judgments and carry out all directions perfectly. Bob Scheutz, the plant manager, told me, “Our senior leadership team had grown accustomed to guiding the mid-level managers – standing right behind them, telling them what to do, when to do it, how to do it, and then providing feedback, positive and negative, on how it went.”

“Why is that a problem?” I asked.

“We’ve gotten so good,” he replied, “that the things we now want to improve are hidden from us – more difficult to see. And if the senior leadership team is still involved in managing every small evolution, then we’re going to miss the next round of improvement opportunities. We need the mid-level managers to feel empowered to step up so that the senior leadership can be liberated to focus on best practices and state of the art innovations in the industry.”

“Would you please give me an example,” I asked.

“When a piece of our closely monitored equipment goes out of service, that automatically triggers a conference call where a key group of people discuss what went wrong, and what to do about it. In previous times the senior leaders would do 95% of the talking. The more junior managers, who are routinely on the scene, would be mostly silent while the senior people worked out the plan. But top leaders are not as intimately familiar with the equipment as the mangers who regularly work with it.

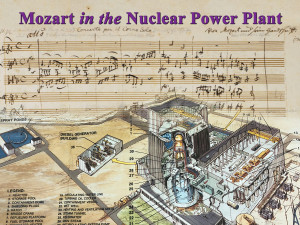

“At our Music Paradigm session all of our people sat inside the orchestra, listening to that Mozart symphony. We all witnessed the conductor illuminate the orchestra’s big picture and show the musicians how all the parts fit together, clarifying how the various roles seamlessly collaborate. He painted a success picture of the music that was easy to understand and possible to implement. We all saw how that empowered and energized the musicians so that they felt ownership of the music and performed with energy, inspiration and accuracy. We seem to have absorbed that lesson pretty well.

“Recently at the plant we had an incident that prompted another conference call. But this time it took only 20 minutes to put the plan together and activate it. And in that call, not a single senior leader spoke. They didn’t speak because they didn’t need to. The mid-level supervisors and superintendents, and the operations shift manager, who’s kind of the guy on site who’s in charge, they put the whole plan together. It was an excellent plan – good enough so that the senior team didn’t even have to weigh in, and make any adjustments. So I mean, that’s a stark example of how The Music Paradigm played an important role in helping us move forward toward our leadership goals. We’re pretty happy,” he concluded, “with our return on investment.”